Drawing Physiognomy: The Complete Zoomorphic Archive

Exhibition by Ross Woodrow (4 April to 16 May 2019) at Gallery 25, Edith Cowan University, Mount Lawley Campus, Perth

The exegetical essay below is available for download as a PDF file on researchgate.net

The exhibition features 95 etchings, all printed on continuous sheets from rolls of Velin Arches (white 300gsm), that ring the circumference of the Gallery. The above panorama shows all but the left entry wall.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Professor Clive Barstow for the invitation to exhibit in Gallery 25 at Edith Cowan University, also to the Curator of the Gallery, Susan Starchen and to Stuart Elliott, whose professionalism made it such a positive experience. In the production of the work, I particularly need to acknowledge Dr Anne Taylor, Dr Tim Mosely, Dr Ali Bezer and Dr Blair Coffey who helped me print the copper etchings. Thanks to those colleagues in the print department at QCA Griffith, particularly Jonathan Tse and Ruth Cho, who gave invaluable help in completing my ambitious mission of printing at this scale.

Installation (detail)

Introduction to the project.

One of the most pervasive and persistent ways that humans seek to find meaning in their physiognomic structure is through comparisons with the form and characteristics of non-human animals. The power of a lion, the majestic grace of a thoroughbred horse, the deceptive delights of a mocking bird or insidious nature of a poisonous gecko can all be projected into the character of a human by a graphic zoomorphism that aligns each of the respective animal physiognomies with a human face to create or imply resemblance.

This exhibition demonstrates the tenacity of this process in the most exhaustive way by presenting over eighty such human/animal comparisons. These derive from the original zoomorphic images of Giambattista Della Porta in the sixteenth century, and the influential versions by Charles Le Brun in the seventeenth century, through to the contemporary comparisons of dog owners and their pets along with familiar internet memes aligning celebrity physiognomies with various animals.

Such zoomorphism has always been seen as amusingly frivolous compared to the later development of anthropomorphism where artists such as J. J. Grandville in the nineteenth century and Walt Disney in the twentieth century managed to convince global audiences that animals, beneath their outward physiognomy, were really people.

The significant time invested in recreating this illusory universe, using that demanding form of material production, etching and aquatint, is not only to expose the importance of the graphic enterprise in making real the intuition that “the great chain of being” exists and humans are but part of a singular animal kingdom but also to signify its fictional and fantastic dimension.

The final counterpoint to the exhibition includes the images that demonstrate the power of art to influence science but often through a negative process of misinterpretation or misrepresentation by reading art as evidence.

The following installation and detail photographs are by Stuart Elliott and subject to copyright.

This exhibition was intentionally devoid of descriptive labels or wall text and the following exegetical essay served to augment the experience of the exhibition by positioning its historical and contemporary context and explaining the choice of sources used for the images.

Drawing Physiognomy: The Complete Zoomorphic Archive. [ Exegetical Essay]

The physiognomic heuristics of reading faces has always been regarded as a major form of non-verbal communication, demonstrated today by the 24 billion selfies uploaded to Google in 2018.[i] Not everyone uploads their image to the social media vortex but many upload multiple images, considering this figure is more than three times the current population of the world. The physiognomic impulse to capture the expressive moment or find characterological insights through the suggestive power of the human face is as old as recorded history.[ii]

Putting on fake whiskers and cat’s ears for a transformative selfie or exaggerated pouting and posturing for a pose, for example, might suggest the frivolous fun aspect of this massive global trend. On the contrary, such roleplay is a fabricated indifference to mask a deep adherence to the physiognomic impulse that defies capture in discursive or scientific terms.

Reading physiognomic features has always been more than serious fun since an understanding of a person’s inner being from external appearance would allow an easy navigation of the social world. As it would facilitate a hierarchical categorization of that world. When the great art historian Ernst Gombrich (1909 – 2001) first wrote about this physiognomic perception; the intuitive, aesthetic response to reading the physiognomy of a person he acknowledged its importance for artists, but as it was soon after the second world war, not unexpectedly, he claimed no universal extension or application of physiognomy as a system of signs for communication or understanding. [iii] At that time Gombrich was obviously not so much concerned with the usual dismissive relegation of physiognomy to common sense but about its power to rationalise common prejudice.

Since recorded antiquity, and across cultures, the impulse to find meaning behind the external appearance of humans has included comparisons with other animals. The Pseudo-Aristotelian Physiognomonica (c. 300 BC) and Polemon’s Physiognomy in both its Graeco-Roman derivatives and Graeco-Arabic versions in Medieval Islam develop theories of physiognomy based on similarity to animals.[iv] The general agreement across the ancient texts on physiognomy was that external appearance was linked to the internal character, form or soul of an individual. In short, physiognomy linked physical appearance with individual psychological disposition and character in humans and a more generic species or type-specific nature in other creatures. It goes without saying, that in both the Classical world and Islamic civilization humans represented the centre or pinnacle of divine creation. Both also developed the idea that each human was a microcosm of the animal world epitomizing infinitely varying degrees of the characteristics found across all living creatures, but Islamic civilization developed this idea more fully and Muslim writers took a greater interest in the animal world than did Classical writers.

David Mitchell is a koala [see: http://davidmitchellisakoala.tumblr.com/ ]

The facial physiognomy of British comedian David Mitchell is patently like that of a koala, which is not necessarily something you would have noticed unless it was highlighted by the numerous parallel web-images of his face and facial expressions aligned with those of a koala. Nevertheless, once such compelling physiognomic resemblance is established there is an attendant urge to imply other associations. In this case the koala’s endearing attributes of impassivity, cuteness and fluffiness easily translates as corresponding character traits of Mitchell, regardless of this being true or not.

In this exhibition I have included a small number of contemporary examples of such human and animal comparisons from the countless examples on the Internet where the human subject is usually a celebrity, or an anonymous pet owner being compared to their dog or cat. Most of the source images I use are from the seventeenth to nineteenth century with the majority falling in the relatively short period from 1790 to 1860 when the ancient aesthetic and mytho-moral foundations of physiognomics transformed into racial science.

This seemingly narrow chronological selection gives emphasis to the pre-photographic period when artists played a key role in the graphic construction of real or imagined correspondences between humans and other animals. Physiognomics and aesthetics were always inseparable, with observation, classification and schematics becoming the fundamentals of an artist’s education since Classical times. This dual mission of both the fields of art and physiognomy to turn observation, instinct, intuition and non-discursive understanding into a method to complement the abstract power of mathematical or scientific systems has made them regular, and in the nineteenth century, very successful, partners in transforming the social world.

By the end of the sixteenth century European artists attempted to codify visual traditions as method and transmit the established body of technical, theoretical and schematic knowledge via drawing manuals. In these manuals, physiognomics played an equal role to proportional and constructive geometry, with human and animal physiognomy and anatomy often linked through comparative construction of resemblance and dissimilitude. The Frontispiece of the second part of Frederik Bloemaert’s influential drawing manual of about 1650 featured the front view of the head of an ox carrying the attributes of painting and drawing; palette, brushes maulstick and inkpot. This image would become the emblem for drawing and feature on various drawing manuals for centuries.[v] Fragments of various drawing manuals or treatises by Rubens were published by Jombert in 1773 and this compilation includes human animal comparisons such as man and ox, man and lion and woman and horse.[vi]

By the middle of the eighteenth century in Europe, however, the woodcut illustrations of human animal comparisons from Della Porta’s Physiognomy of 1586 were in wide circulation and these images would dominate any discussion of comparative studies of human and animal physiognomy in drawing manuals and physiognomy studies until the end of the nineteenth century. These Della Porta woodcuts [figure 1] varied greatly in the quality of delineation and production, with the most compellingly and aesthetically accomplished images being created by Charles Le Brun (1619 – 1690) [figure 2] who as Royal Painter dominated art in France in the last quarter of the seventeenth century. It was Le Brun’s drawings of human expression and human/animal comparisons that were used by Johann Caspar Lavater (1741-1801) in his seminal volumes on physiognomy.

It is difficult today to imagine the impact of the early deluxe volumes Lavater produced, as his Essays on Physiognomy from 1775 to 1803.[vii] Difficult, primarily because it is the experience of examining these volumes which reveals that they did not contain a new physiognomic theory but are graced with hundreds of engravings, matched in scale and quality by few publications in the eighteenth century. [See figures 4 and 5] Lavater targeted and employed the very best European graphic artists of the age including; Henry Fuseli (1741 – 1825), William Blake (1757 – 1827), Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki (1726 - 1801), and Johann Heinrich Lips (1758 – 1817) who Lavater had taught as his drawing master. In fact, as I have noted, Lavater’s Essays on Physiognomy can be read as part of the drawing manual tradition. [viii]

It could also be argued that in the Classical tradition of art, physiognomy became an essential element and theoretical premise for much painting and sculpture. If a marble sculptured bust of a Roman noblewoman captured her inner or living character it would logically follow that this essence must be able to be read through external appearance. Polemon in his Physiognomy could discuss the quality of Emperor Hadrian’s “beautiful and luminous light” with reference to his imperial eyes that Polemon had almost certainly only seen in marble sculptures.[ix] Indeed works of art became a singularly important source for physiognomists and almost all the historical examples of faces examined in Lavater’s major study came from portrait paintings and sculpture, mostly via engraving.

It was taken as a given that portrait sculpture could capture and retain the readable signs of character. For example, Francis Howell, in his 1824 translation from the Greek of the descriptions of character types by Theophrastus added contemporary “physiognomical sketches” and acknowledged at the beginning of the Preface the superiority of ancient sculpture over text in its capture of physiognomic essence.

The marble that has retained upon its fleshy surface the frolic smile, or the pettish frown, or the haughty glance, that was fixed there by the hand of art twenty centuries ago, awakens in our bosoms a more vivid sympathy with the distant and forgotten members of the great family of man, ---gives us a fuller conviction of the permanent and perfect identity of our species, and places us in nearer communication with past ages, than volumes of the grave records of history.[x]

Portrait painters who seek to capture essence of character through physiognomic features, or more usually today, photographic likeness, follow this seemingly pre-programmed impulse to assume characterology can be read morphologically. The innate physiognomic impulse that Gombrich identified as physiognomic perception, Lavater also recognised and broadened into his conception of physiognomic sentiment which he claimed could be cultivated in physiognomists including artists.

Lavater understood the problem with all imitative or mimetic visual representations of the world in that the object or image created expressed the inner view or individual interpretation of the artist as much as any accurate resemblance to the world. Lavater developed, the part-solution, of a mechanical capture of likeness through his ‘silhouette chair’ or machine that used tracing of cast shadow to replace interpretative drawing of contour from observation by the artist. [figure 5] Although the shade or silhouette became a popular craze across Europe and American well into the nineteenth century, the shade had limited aesthetic appeal beyond recording profile likeness. When it came to morphological comparisons with animals the silhouette was never used by Lavater. His most famous attempt at illustrating a graduated morphological sequence of the animal world was his phylogenetic development of the poet Apollo from a lowly frog in 24 steps. [figure 6]

Figure 5 Lavater, A Chair for Taking Shades. Left is the empty chair from the popular Holcroft edition wrongly suggesting a lens where there should be a sheet of glass to trace the silhouette. The centre image is from the first edition and the last from a Dutch translation.

Figure 6 Lavater, Frog to Apollo 1789

This was also, not coincidentally, a gradation joining the polarities of beauty and ugliness, since Lavater had read the aesthetic theories of Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768) who placed the Apollo Belvedere marble in the Vatican (which was a Roman copy of a lost Greek bronze) as the quintessence of beauty. In his Essays, Lavater quoted extensively from contemporary aesthetic theorists such as Herder and Winckelmann and earlier writers such as Leonardo Da Vinci and Charles Le Brun in keeping with the aesthetic, philosophical or theological nature of his enterprise.[xi] At the historical moment that Lavater was preparing his last volume of the German edition of his Essays the Dutch physiologist Pieter Camper (1722-1789) wrote to him in 1776 reporting his discovery of the “facial angle” that could measure the separation point between animal and human. Camper had given a series of lectures at the Amsterdam Academy from 1774 to 1782 where he outlined his natural scientific research on the facial angle for its utilisation in art. Camper also uses the Apollo as the pinnacle of physiognomic facial form, but he begins with the ape rather than the frog.[xii] [figures 7 and 8]

Figure 7 Pieter Camper, Thomas Kirk engraver, Ape to Apollo TAB I, 1794.

Figure 8 Pieter Camper, Thomas Kirk engraver, Ape to Apollo TAB II, 1794.

Camper’s ape to Apollo would relegate Lavater’s frog cycle to an amusing appendix to the understanding of the separation of humans from the rest of the animal world. Camper’s facial angle was utilised by Lavater as the analytical basis for all further morphological development series, although the frog to Apollo diagram survived through the nineteenth century in the second French edition and numerous single volume nineteenth-century Lavater editions abridged from the 1789 three-volume Thomas Holcroft translation of the first German edition.

Camper’s diagram is no more scientific than Lavater’s construction since they are both based on the aesthetic judgments of antiquity and not any proven facts or data. The Apollo becomes the arbitrary top of a scale that is illogically built downwards to end at different animals. What gave the Camper engraving ascendency, apart from the larger scale and superior quality of the drawing, was the use of the quantifiable measure in the facial angle or line. The ideal measured 100%, with 70% denoting the demarcation point between human and animal. The arbitrary nature of this selection of a facial angle which was created by drawing a line horizontally from ear opening to under the nostril and vertically from the most protruding point of the forehead to the front edge of the upper jaw was elided by the ideological and theological confirmation of the results. Later in the nineteenth-century when the facial angles of Australian Aboriginal features and skulls were measured the high forehead meant that the angle did not at all fit the expectation for animality much to the consternation of European anthropologists.

Measurement was the key Enlightenment tool of classification and control and the physiognomic insights, innate or developed, presented by Lavater were no match for the empiricism of a system of measurement and experimental evidence presented early in the nineteenth century by Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828) and his associate Johann Gaspar Spurzheim (1776-1832) during the development of what became known as phrenology. Gall discovered through dissection and experimental deduction that mental and motor functions are localized in discrete parts of the brain but wrongly assumed that the location of these mental capacities could be detected from external physiognomic structure of the head. Naturally enough a large forehead, as Camper had already “proved” designated abundant intellect and the concept of “highbrow” culture emerged. It turned out to be deluded, but Gall managed what Lavater never did by making definitive diagnostic linkage between sign and symptom or propensity. During the brief fifty or so years of acceptance of phrenology as a science, and long after, it was possible for phrenologists to read heads and identify the strengths and weaknesses of character, along with propensities and abilities in individuals and of course advise the best educational or correctional strategies to take to improve their better nature.

Nevertheless, throughout the period of peak recognition of phrenology as a science from 1820 to 1870 there remained a strong devotion in Europe, America and Australia to Lavaterian physiognomy since it was less doctrinaire and most of all offered a simple confirmation, or otherwise, of one’s physiognomic sentiment or insight on first encounter with a prospective employee, servant or spouse and the countless pocket editions of Lavater no doubt proved handy to quickly inspect the character of fellow coach travellers.

Almost all the twenty or more pocket Lavater editions that I have examined include Della Porta’s human animal comparisons at the back, presumably offering a much more secure theoretical basis for observation than the mathematical abstraction of a facial angle. However, there were a number of comparative human and animal publications during this period, when phrenology was at its peak, that explicitly present comparative physiognomy as an alternative to phrenology or interpret Gall and Spurzheim as part of Lavater’s physiognomic program.

I have excluded phrenology books in sourcing my images and follow the physiognomic tradition beginning with Della Porta, using the edition: De hvmana physiognomonia Ioannis Baptistae Portae Neapolitani libri IV : qvi ab extimis, quae in hominum corporibus conspiciuntur signis, ita eorum naturas, mores & consilia (egregiis ad viuum expressis iconibvs) demonstrant, vt intimos animi recessus penetrare videantur Rouen: Berthelin, 1650.

The examples I source from Le Brun come mostly from volume nine of the French Moreau edition of Lavater from 1806 in which the first eighty pages consist of Lavater’s writing on animal physiognomy, including his frog to Apollo cycle. The rest of the volume is made up entirely of Le Brun’s writings on physiognomy along with his suite of drawings of human animal comparisons after Della Porta.[xiii] My frog to Apollo image comes from a nineteenth-century Holcroft single volume edition of Lavater and Camper’s diagrams are taken from the first English translation of Camper by Thomas Cogan.[xiv]

Several examples are sourced from the physiognomical sketches in Francis Howell’s Characters of Theophrastus. The largest proportion of the images in the exhibition come from two sources: Cabanis, Porta et. al. (Anon) Nouveau Lavater complet, réunion de tous les systèmes pour étudier et juger les Dames et les Demoiselles ... d'après Cabanis, Porta, Spurtzheim, Gall, Broussais, et autres savans anciens et modernes Bruxelles: Librairie encyclopédique de Périchon 1840; and, James W. Redfield, Comparative Physiognomy: Or, Resemblances Between Men and Animals, New York: Redfield, 1853. The isolated single animals on the sheets are all sourced from twentieth-century drawing manuals.

The bizarre nature of many of the human and animal comparisons I’ve selected from all sources does raise the question of the seriousness of intention in their creation or the humourless reception or otherwise by their contemporary audiences. Charles Le Brun’s published lectures from the end of the seventeenth century onwards, where he promoted and illustrated the idea that expression was a symbolic form of language, remained of fundamental interest in the training of artists until well into the twentieth century, at least if drawing manuals are used as a guide. There is no doubt that Lavater was taken seriously with his Physiognomy making significant impact across art, literature, medicine and science. Charles Darwin read or reread Lavater’s treatise in researching his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) where he “uses Lavater’s idea of physiognomic judgements as instinctive acts to demonstrate the analogous emotional expressions in humans and animals.”[xv]

Editions of Lavater were held in all major libraries in the nineteenth century including the Royal Academy in London and the Victoria and Albert Museum. The edition of The Characters of Theophrastus I’ve consulted is a cancelled duplicate copy from Georgetown University Library and originally in the Catholic Loyola Seminary Library, Shrub Oak, New York. Even more revealing the Redfield on Comparative Physiognomy I have used is also an ex-library copy from the US Navy Lyceum, the highly regarded officer school at the Brooklyn Navy Yard established in 1833.

Figure 9a Frontispiece for: Nouveau Lavater complet, réunion de tous les systèmes pour étudier et juger les Dames et les Demoiselles Paris 1840

Figure 9b Frontispiece, Nouveau Lavater complet, réunion de tous les systèmes pour étudier et juger les hommes et les jeunes gens …etc Paris 1838

A folding frontispiece for the 1840 Nouveau Lavater for the study of women and girls is a gender reversal of

the earlier, 1838 version on the study of men and boys and shows the three areas of authority quoted in the text, namely, Lavater, Gall and Cabanis. [figures 9a & 9b] The latter theorist, Pierre Jean Georges Cabanis (1757 – 1808), had revitalised the ancient theories of the temperaments by suggesting a unity between the physical and mental and this materialist link between sensibility and the nervous system gained traction in France. Throughout the text in these popular illustrated volumes references are made to these three and the other authors mentioned in the introduction and the essays presume a broadly expansive knowledge of the fields of both physiognomy and phrenology. Interestingly when character types are illustrated with animal comparisons there is no detailed comparative analysis of the lithographs, but it is assumed that readers will see the analogous connections “through an air of resemblance, points of sympathy and contact”.

The tone of the writing in the Redfield Comparative Physiognomy seems to be the most outrageously extreme to the point of parody but Redfield, who was a medical doctor, published two earlier volumes on a new system of physiognomy in which he explains the earnestness of his desire to find alternative systems to phrenology.[xvi] However, the hard evidence that his often-disconcerting alignment of humans and animals was a serious-minded enterprise is the extended discussion of his book in the April 1868 issue of The Anthropological Review, published by the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland.[xvii] The article titled “Physiognomy” includes the following praise.

We have to thank Mr. Redfield for a very extraordinary and original work, which if not a contribution to exact science, still is to sound knowledge, and an opening to a world which will be new to many of us, although his book is founded on observations and analogies which the acute in all ages have perceived. Comparative Physiognomy, or the Resemblance between Man and Animals, is the title of the book. With but little system, the author proceeds to give many examples of resemblances in form and character: thus, we have beasts, birds, reptiles and fishes, and their human prototypes. His work is illustrated by a large series of expressive woodcuts, which we wish we could quote as easily as his words; but not to leave our readers in the dark altogether, we have copied some of them to illustrate the author. No description can give an adequate idea of the merits of the book: buy it, reader, and judge for yourself.

The illustrations presented in the “scientific” journal bear only passing resemblance to the wood-engravings in Redfield’s book.

Two examples will make this point clear. [figure 10]

Figure 10 Top. original Redfield wood-engravings 1853. Bottom The Anthropological Review copies 186

The relatively few sources used would hardly seem to qualify my selection as the complete zoomorphic archive, which of course would be an impossibility, but these offer sufficient number and variety to serve the purpose of the exhibition to engage viewers in a unified morphological field so vast that it demands a significant investment in physiognomic selection and rejection. The unity in this case comes from the fact that all the images are redrawn, etched and aquatinted with black ink on the same paper substrate. This unifying idiom contradicts the original source in each case since they were originally all printed with woodcut, engraving or lithography. The enveloping installation of human animal comparisons is interrupted by a single framed print. This is an original etching on hand-laid paper from 1669 by an anonymous engraver after Arnoldus Montanus titled 'Baviaan Orang-Outang”. It shows a highly anthropomorphic representation of an ape couple. This contradicts the zoomorphic strategy of projecting animal characteristics onto human physiognomy as it demonstrates the great difficulty artists had in overcoming the urge to see animals as humans. This interruptive addition to the exhibition is not just a contradictory foil to the zoomorphism it is a key to understanding that this archive can be read as a microcosmic epitome of animal nature created through the idiomatic syntax of etching.

Anon. after Arnoldus Montanus Baviaan Orang-Outang etching on laid paper 1669.

Copyright © Ross Woodrow --All Rights Reserved

NOTES

[i] Google official blog: https://blog.google/products/photos/google-photos-one-year-200-million/

[ii] Ellis Shookman, The Faces of Physiognomy: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Johann Caspar Lavater Camden House, 1993 esp. 64.

[iii] Ernst Gombrich, "On Physiognomic Perception," in Meditations on a Hobby Horse and Other Essays on the Theory of Art, London, 1963. His observations first published in “Art and Scholarship" (1957),

[iv] Simon Swain ed. Seeing the Face, Seeing the Soul; Polemon’s Physiognomy from Classical Antiquity to Medieval Islam, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007 esp. 252.

[v] Jaap Bolten, Method and practice: Dutch and Flemish drawing books, 1600-1750 Landau: PVA 1985 50

[vi] Bolten, 108.

[vii] The three major editions of Lavater are: the first German edition, Physiognomzsche Fragmente, zur Beforderung der Menschenkenntniss und Menschenhebe, 4 vols. (Leipzig, 1775-78); the French edition, Essai sur la physionomie, destiné a` faire connoitre I‘homme et a le faire aimer 4 vols (The Hague, 1781 – 1803); and the Henry Hunter published English edition, Essays on Physiognomy Designed to Promote the Knowledge and the Love of Mankind, 3 vols bound across 5 books (London, 1788 – 1799). Through the nineteenth-century over 150 editions in various languages and forms were published. The English versions were mostly dependent on the 1789 Holcroft translation of the abridged German edition rather than the Henry Hunter edition which derived from the more developed French edition.

[viii] Ross Woodrow, “Lavater and the Drawing Manual” in Melissa Percival and Graeme Tytler eds. Physiognomy in Profile: Lavater's Impact on European Culture Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2005 (71 – 93) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/29464296_Lavater_and_the_Drawing_Manual

[ix] Swain, 208.

[x] Francis Howell, The Characters of Theophrastus; translated from the Greek and illustrated by physiognomical sketches, London: Josiah Taylor 1824 xi.

[xi] On Lavater’s connection with connoisseurship see: Melissa Percival, “Johann Caspar Lavater: Physiognomy and Connoisseurship” Journal of Eighteenth-Century Studies, Vol 26, Issue1 March 2003 (77-90)

[xii] The only comprehensive analysis of the Lavater’s frog cycle I’m aware of is: Uwe Schögl, Wien “Vom Frosh zum Dichter-Apoll Morphologische Entwicklungreihen bei Lavater” in Gerda Mraz und Uwe Schӧgl eds. Das Kunstkabinett des Johann Caspar Lavater Wien: Bӧblan Verlag GEs.m.b.H. & Co. KG. 1999 (164 – 171) [I’m indebted to Dr Faye Neilson for her translation of this work in 2004.]

Writing on Camper’s ape to Apollo typology is much more extensive and since the publication of Miriam Claude Meijer’s Race and Aesthetics in the Anthropology of Petrus Camper (Amsterdam 199) there has been concerted attempts to moderate the view that Camper’s diagram had racial motivation or intention. A summary of this view that Camper inadvertently established racial science with this diagram is in: David Birdman Ape to Apollo: aesthetics and idea of race in the 18th century, London: Reaktion Books, 2002 201-209. It does seem to defy logic to suggest that an ascending scale of beauty and morphology from 0% to 100% was not primarily hierarchical.

[xiii] Johann Caspar Lavater (M. Moreau) L'art de connaitre les hommes par la physionomie Paris; Chez L. Prudhomme, l'un des iteurs ... 1806. From page 84 contains: Charles Le Brun Dissertation sur un traite de C. le Brun, concernant le rapport de la physionomie humaine avec celle des animaux. Paris: Calcographie du Musee Napoleon. A later Moreau edition published in 1835 also includes Le Brun’s material.

[xiv] Petrus Camper (T. Cogan trans) The works of the late Professor Camper, on the connexion between the science of anatomy and the arts of drawing, painting, statuary, etc. London: Dilly, 1794.

[xv] Lucy Hartley, Phyiognomy and the Meaning of Expression in Nineteenth-Century Culture, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2001 149

[xvi] James W. Redfield, Outlines of a new system of physiognomy New York: Redfield 1848 (and 1853 ed). Also,

The Twelve Qualities of Mind, or, Outlines of A New System Of Physiognomy, No. II, New York : J.S. Redfield 1850

[xvii] Vol. 6, No. 21 (Apr. 1868), pp. 137-154

APPENDIX I

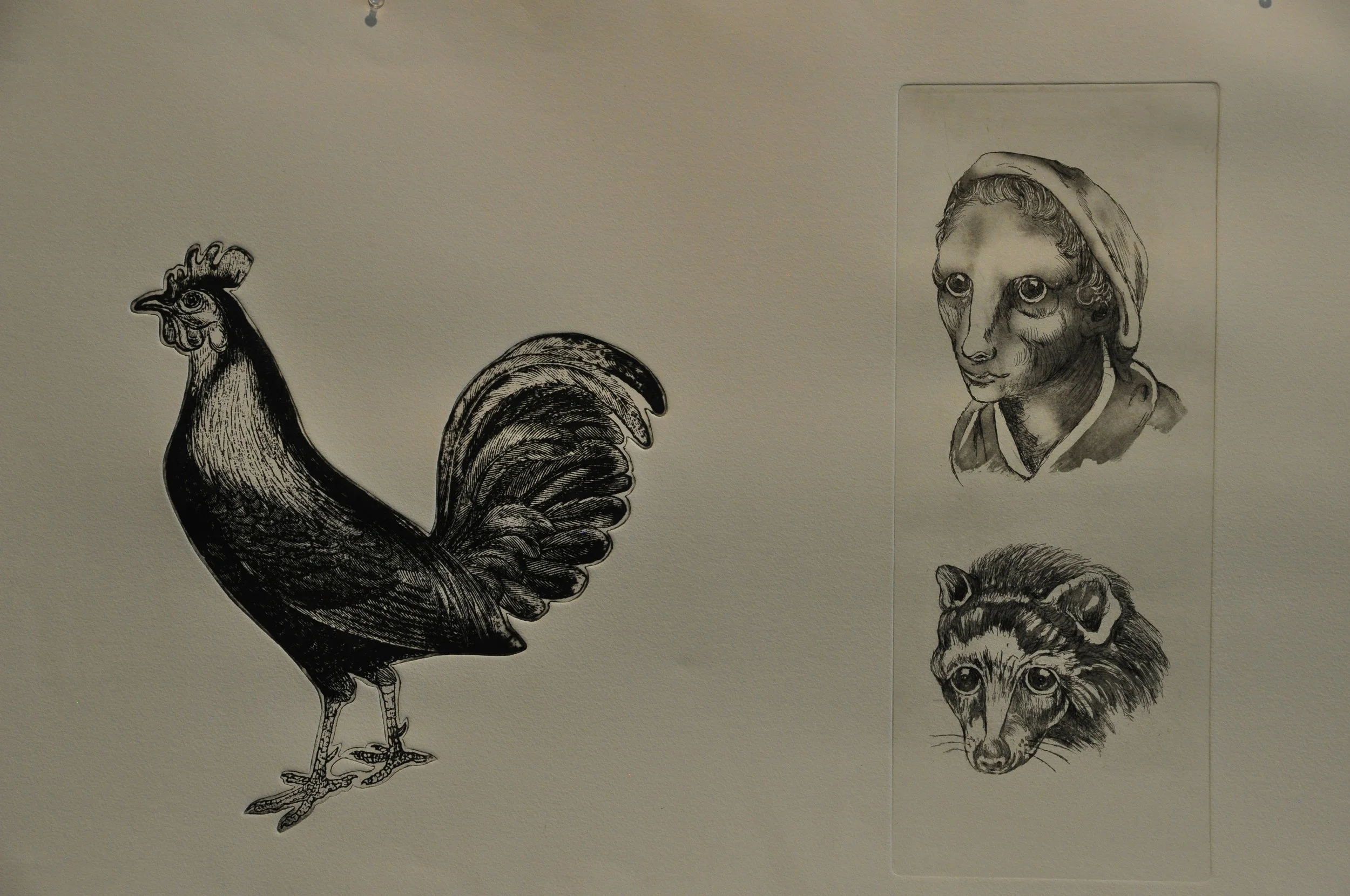

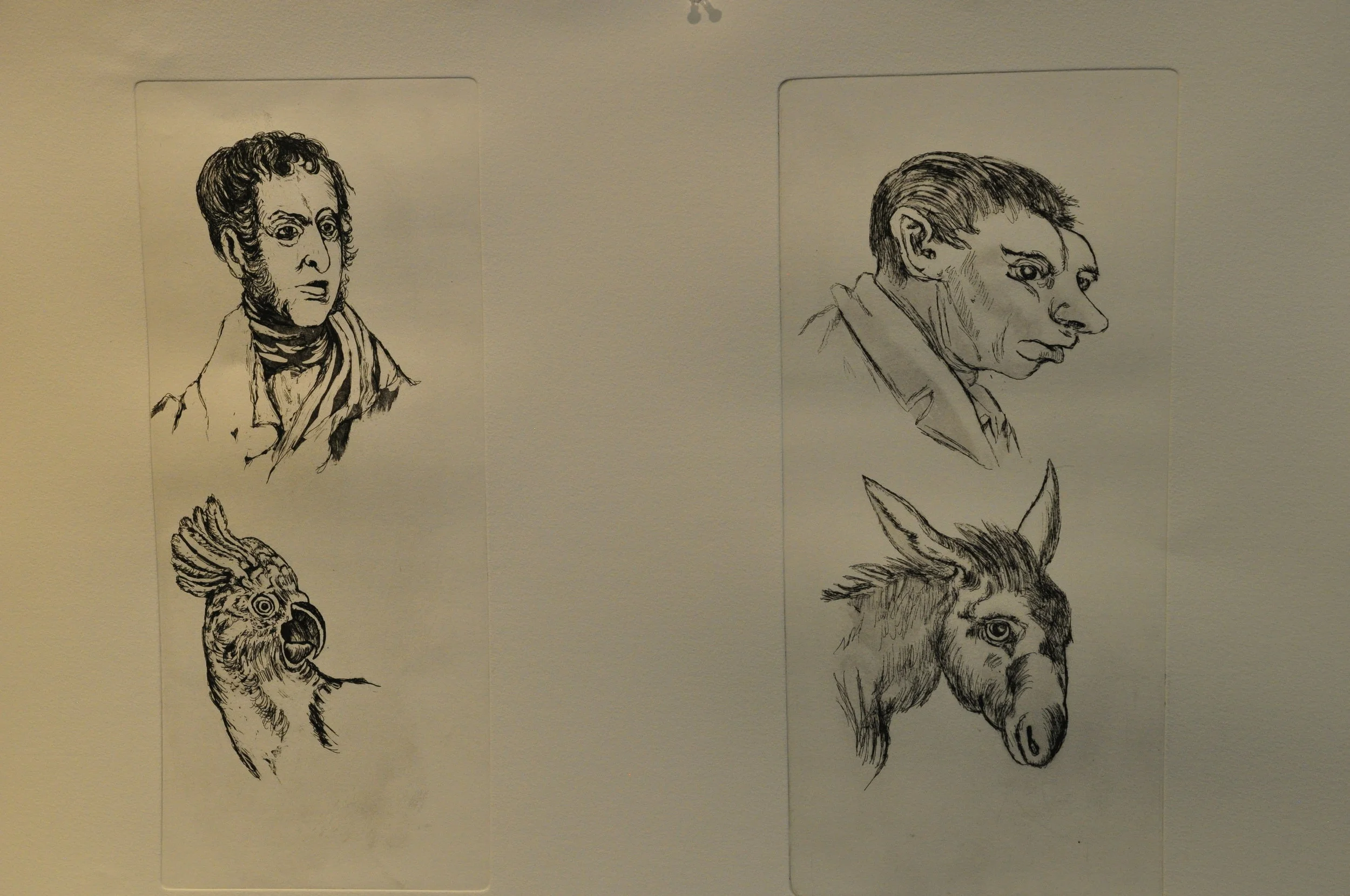

Some of the individual plates are shown below:

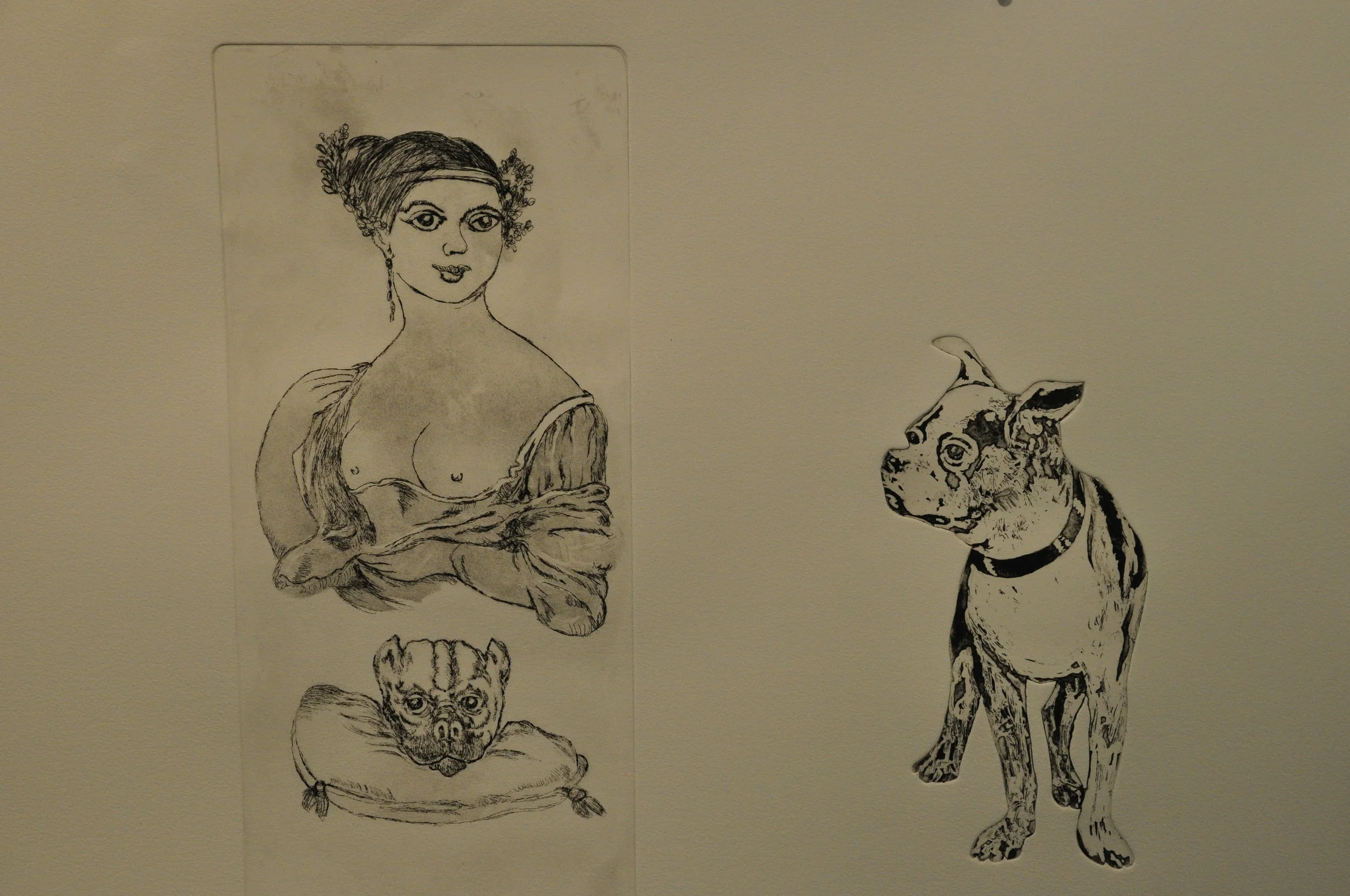

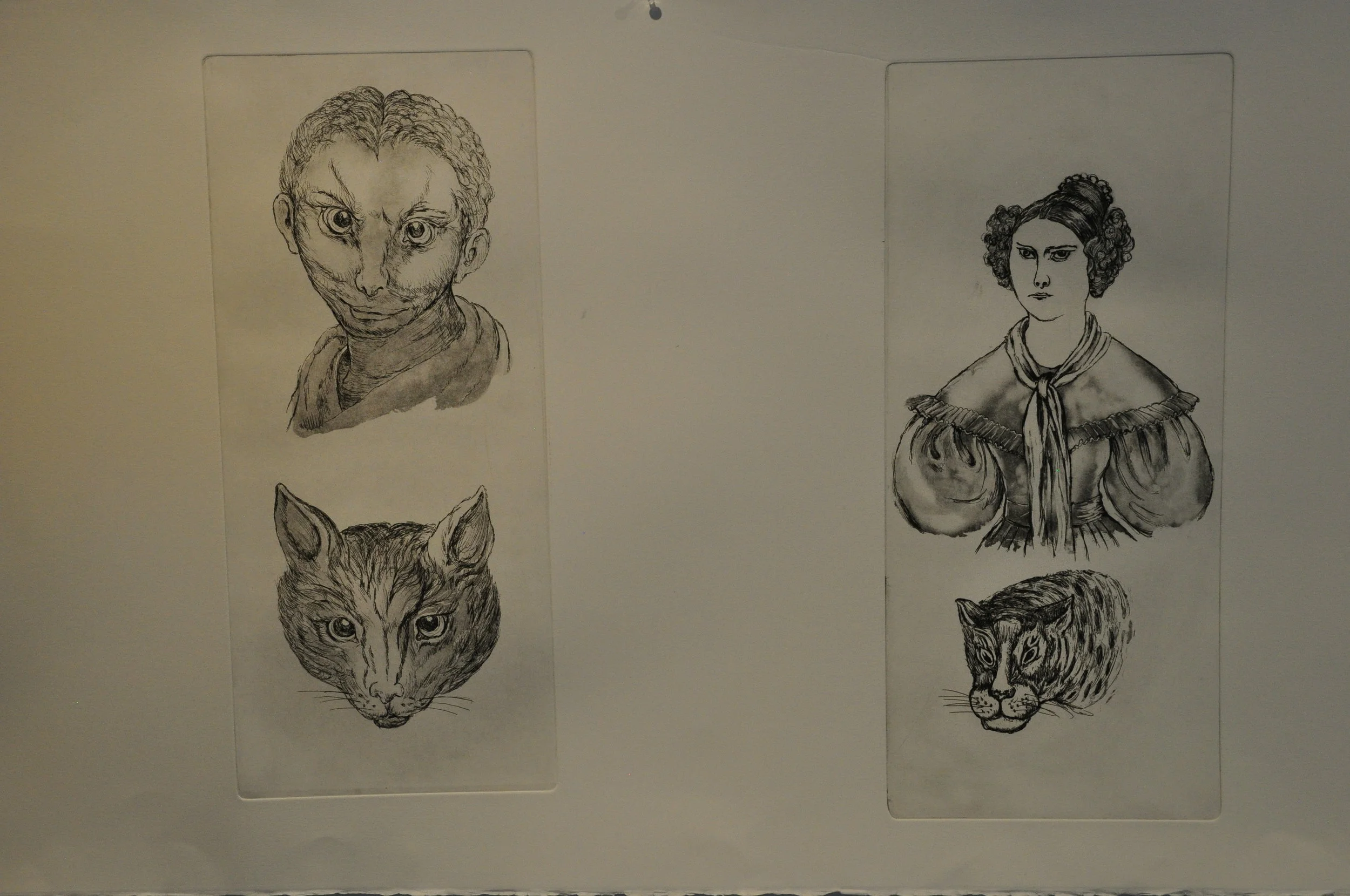

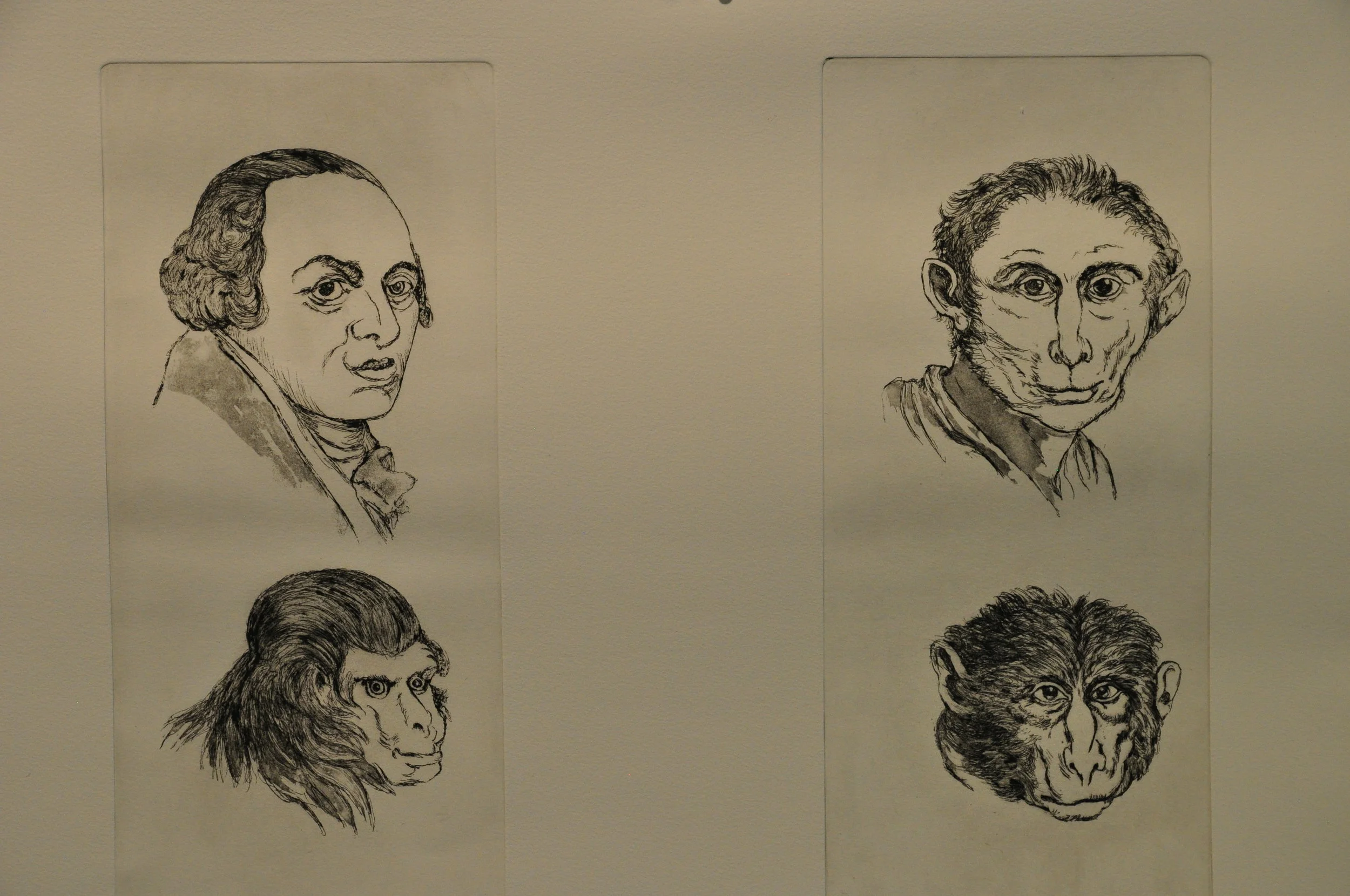

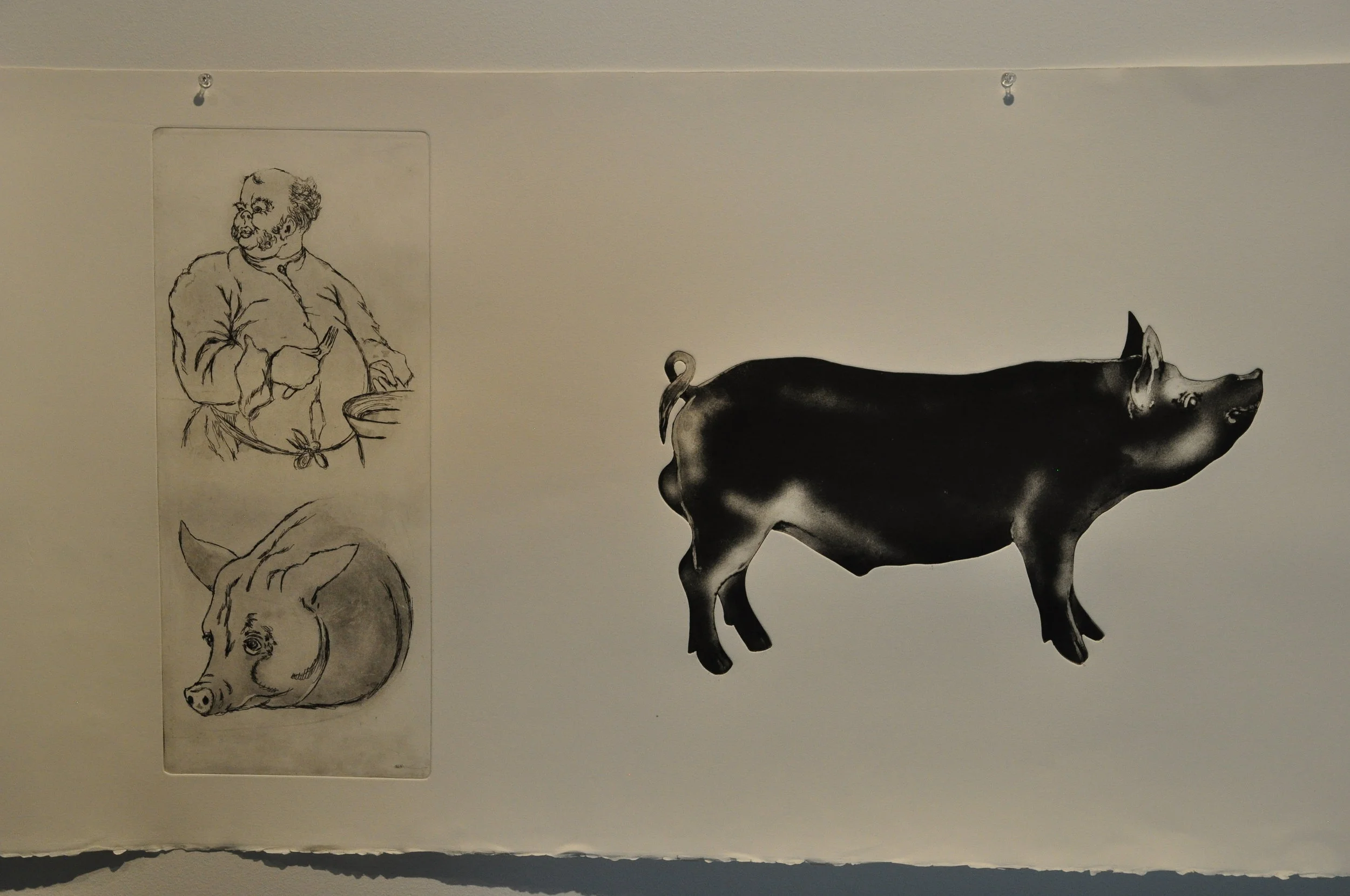

Human and animal resemblance Five copper-plate etchings each c. 45 x 20 cm.

Human and animal resemblance Five copper-plate etchings each c. 45 x 20 cm.

APPENDIX II

Production of the work.

To create a continuous eight-metre sheet of etchings on an etching press with a bed only 1.5 metres long you need: four printmakers, a sky-rig, and about four hours of wiping plates and setting and resetting the press. (photography by Jonathan Tse ) Queensland College of Art Printmaking Studios.

The final roll coming off the press. This completes over 40 metres of running wall sheets of etchings. (photography Blair Coffey)

The sheet hoisted up to dry.

Copyright © Ross Woodrow --All Rights Reserved

![Figure 3 Thomas Holloway, engraving after Rubens, 1788 [original image 17.8 x 13.1cm - plate 26.8 x 22.5cm] Hunter Lavater Vol. 1 25.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b9e00fd506fbe9caf83a4b6/1554381588029-5JO36JIIEIANV6WENU9S/Untitled-7.jpg)

![Figure 4 William Blake, Spalding, engraving [original image 9.6 x 6.3cm - plate 13.2 x 10.1cm] Hunter Lavater Vol. 1, 1789 225.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b9e00fd506fbe9caf83a4b6/1554381586802-ALV2Y3KEAFGOEIASN9RH/Untitled-6.jpg)