Graphic Australia: Prints by Ross Woodrow

(27 May – 17 June 2011) Curated by Gail Heidel. Thomas Hunter Project Space, Hunter College, The City University of New York, Lexington Avenue between 68th and 69th St.,.New York, NY 10065

Ross Woodrow Origin of Modernism lino print on rag paper, 690 x 1060 mm. Edition of 5.

This large lino print interlocks the private and public using generic, banal sources. Both figures are directly taken from drawing manuals and the Morris Minor is based on the original 1948 advertisement for the car. The cup is the familiar Willow Pattern. Although the print was made in 2010 it evokes Australia’s first modern press sensation involving adulterous sex and death on the banks of the Lane Cove River in Sydney, namely the Bogle-Chandler case. In 1968/69 when I was at art college experimenting with abstract painting we used to make trips around Brisbane in a beaten up Morris Minor belonging to an anonymous co-student (Keith Bradbury).

On first glance at the work in this show it might appear that the exhibition title is misleading in its claims to represent “Australia”.

Apart from a few kangaroos, a North Australian or Queensland house, and a generically urban Australian city, there are no iconic Australian emblems or landscapes. This is where the “Graphic” part of my title becomes significant. None of these images are drawn from life nor, significantly, are they sourced from the internet; that global archive for the image economy today. Instead, my imagery is almost exclusively sourced from graphic representations in nineteenth-century popular texts and drawing manuals in my library. Such sources represent a comprehensive range of images that shaped Australian narratives and desires for a significant part of the nation’s history. All of these sources; the illustrated magazines, storybooks and drawing manuals, were printed in Europe or the United States.

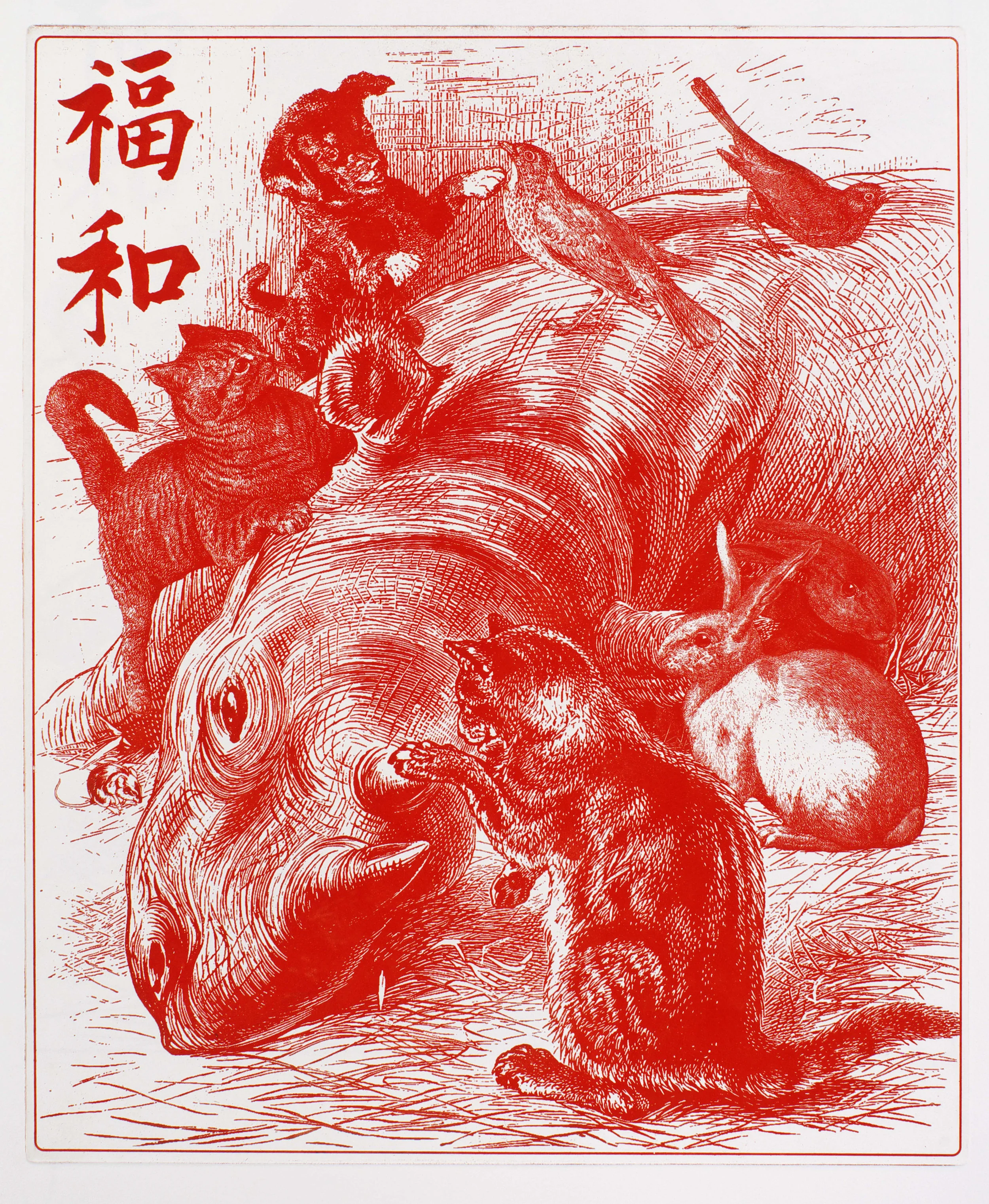

Because the sources generally predate the 1960s, my images evoke an Anglo-American Australia, since it is only in very recent history that Australian visual culture has embraced Indigenous history, art and knowledge. My strategy is not a simple re-imagining of discarded or dead graphic images through changes in context, scale, composition or juxtaposition since I attempt to reinvigorate their potency through process. For each print, be it etching, woodcut, linoprint or lithograph, I match the expressive qualities of the process to the particular image. Although every printmaker does this, in my case I am not particularly concerned with making prints that express the unique properties of a particular medium or foreground their so called “print qualities”. For me the success and visual impact of a print will result from an inseparable enfolding or interlocking of process and image to create an implied narrative. Often the production processes are as multilayered as the sources for the images. For example, Special Friends is a compilation of eight nineteenth-century engravings, an image from a drawing manual and the Chinese characters for “Happiness” and “Harmony,” sourced from a rubber stamp kit purchased at the Saatchi Gallery during its large Contemporary Chinese Art exhibition in London in 2008. The lack of intervention in the source images is evident in the different fine or course engraving styles. The narrative integration of the various elements has been achieved through digital drawing or computer manipulation of the components. The final composition was printed on clear plastic for transfer to a photosensitized zinc plate which was then etched and printed in the conventional way on an etching press.

The same complex stratification of processes characterises the large etching Pretty Polly that brings together a tiny engraved colophon from a German edition of Lessing’s Laocoon and an absurd parrot from Sidney Nolan’s painting Pretty Polly Mine. The domestic drama in the large linoprint The Origin of Modernism is constructed using two banal figures from a drawing manual and the original engraved advertisement for the Morris Minor motor car.

To create something new from the long forgotten, the overlooked, or vernacular image is a fraught quest since sweetness, dread and sentiment have been the essence of the popular image since the nineteenth century at least. Now that the shelf life of postmodern irony has passed, the task of using materiality to surmount the numbing sincerity of a kitsch image is further complicated. As it also is by the dominance of screen and digital images which has confused any accepted pictorial hierarchies and erased the distinctions between private and public images.

In this exhibition I test the limits of the material image by taking the printmaking process a further step into the purely digital realm and creating an installation that facilitates the direct encounter between digital technological and material image production. This is not to suggest a defining polarity between computer and hand generated prints but to demonstrate the infinite mutability of a vital image to adapt to the processes that give it life.

After Party linoprint on rag paper 950 x 730mm Artist’s Proof. Edition of 6.

Pretty Polly etching and aquatint (zinc photo-plate) 900 x 500 mm. Artist’s Proof.

This large plate is based on a small colophon of a woman in a nineteenth-century copy of Lessing’s Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry . The parrot is directly taken from Sidney Nolan’s painting of Pretty Polly Mine.

Special Friends (or Happiness and Harmony) etching and aquatint (zinc photo-plate) 590 x 490 mm. Artist’s Proof.

This etching is built from a single image from a nineteenth-century children’s magazine which showed a cat that had befriended the rhino at the London Zoo. (I documentary image it was claimed) I couldn’t resist upping the ante and bringing a a good sampling of other friends into the scenario. The Chinese characters signify happiness and harmony and have a similar or related meaning in Japan.

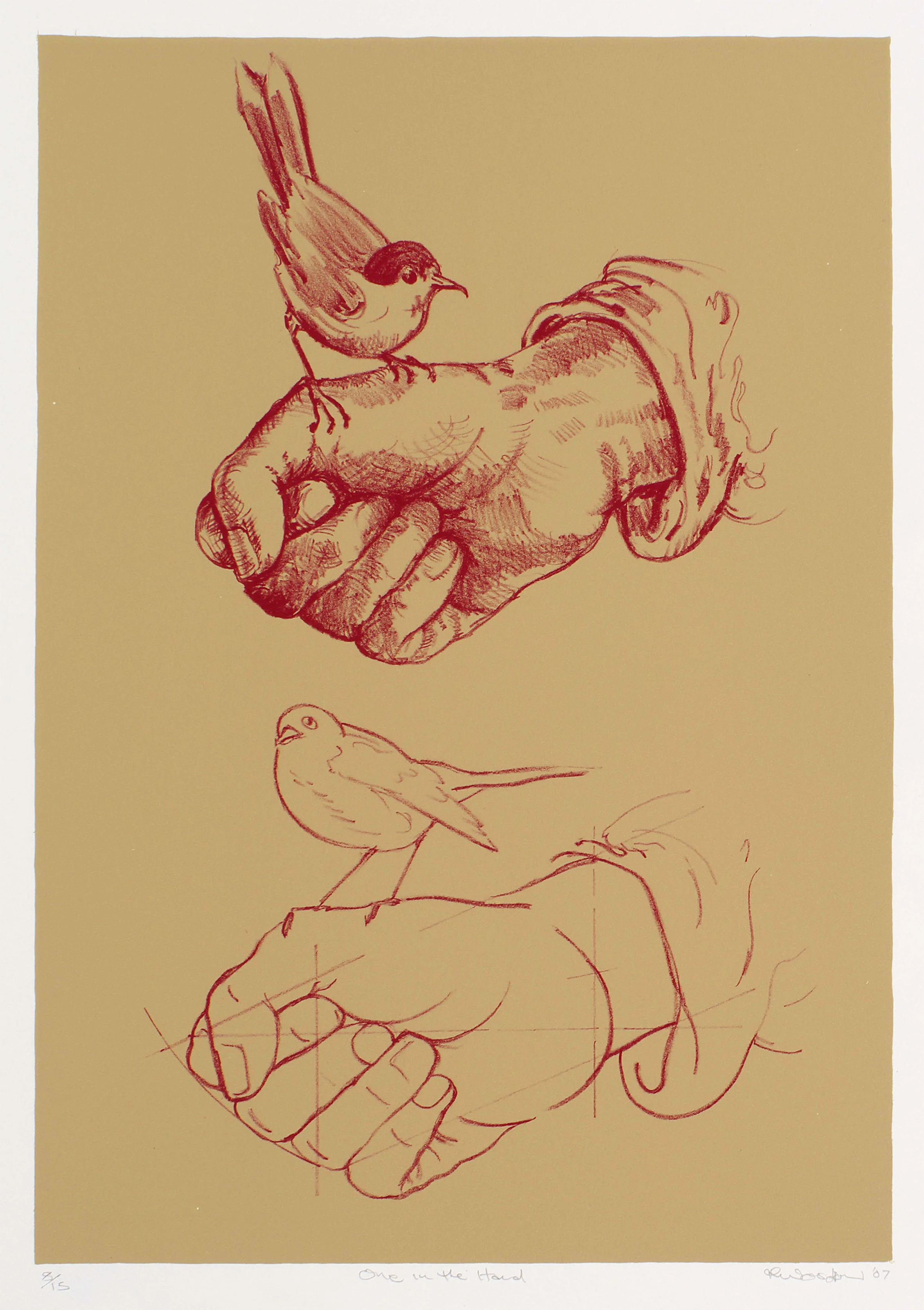

One in the Hand lithograph (Printer, Satoru Itazu, Tokyo) 415 x 280 mm. Edition of 15.

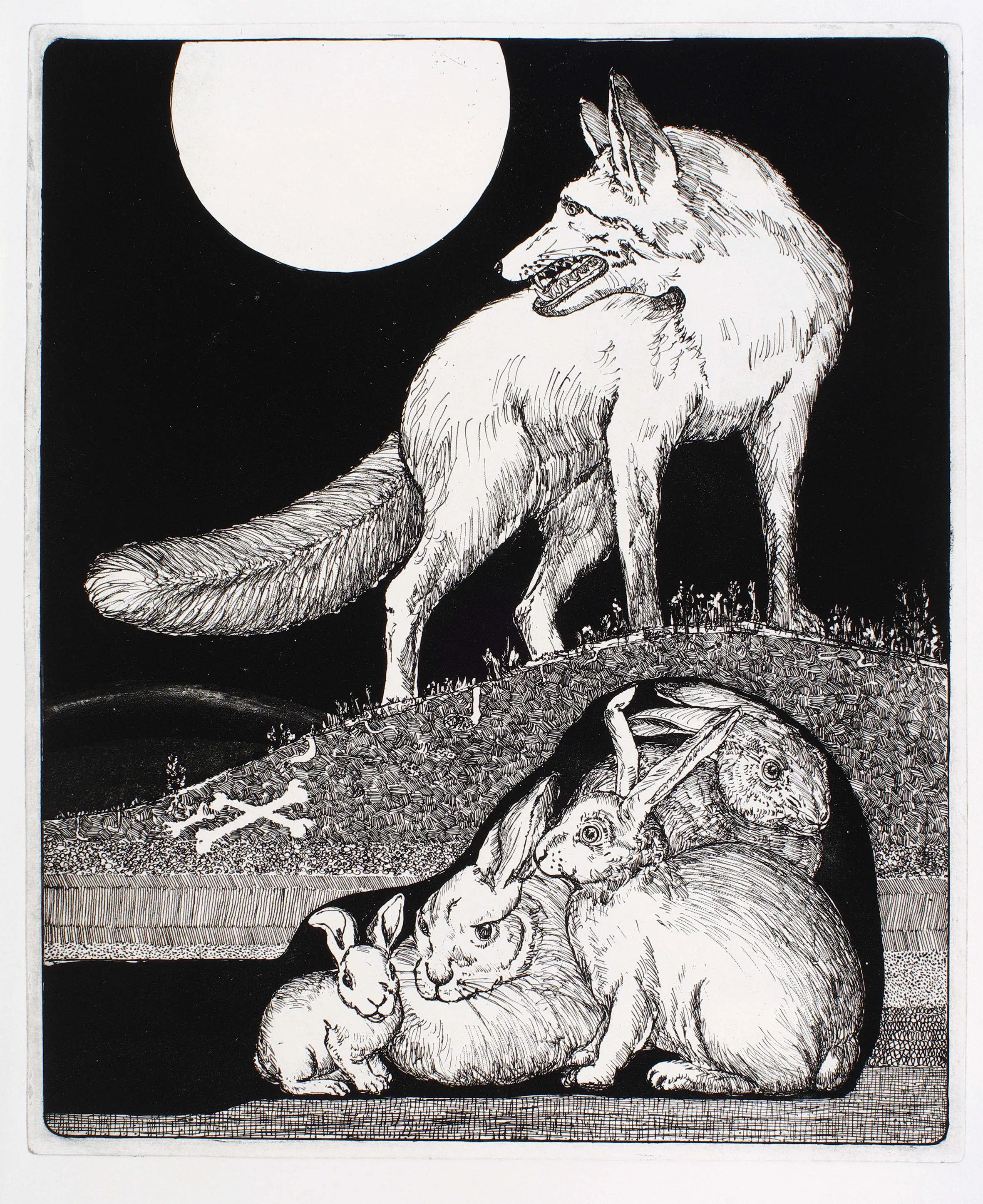

Safe Underground etching and aquatint (zinc plate) 590 x 490 mm. Edition of 5.

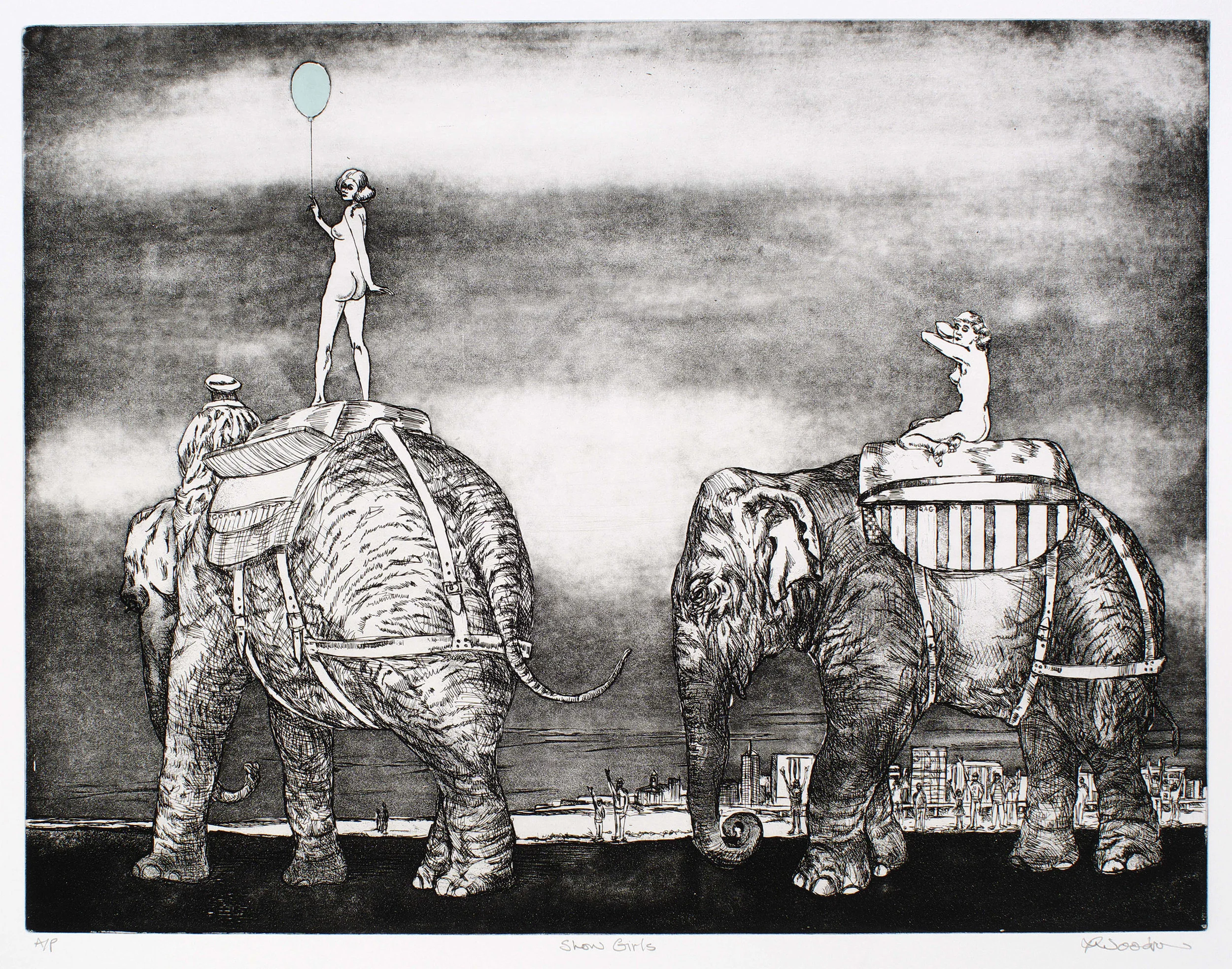

Show Girls etching, aquatint and chine collé (copper plate) 490 x 640 mm. Artist’s Proof.

The elephants are sources from a German manual on drawing animals and the “girls” from figure drawing manuals. The blankets carry the names of the elephants “GOMA and QAG which are the cultural icons across the river from Brisbane city, in the background, with the crowd naturally excited to see the show girls. When I produced this etching it was soon after the Gallery of Modern Art in Brisbane had opened and many were disappointed to find that it was the same crowd-pleasing fare that was being served up. In the eight or so years since making this print nothing much has changed with GOMA, like so many public galleries, finding that when the imperative is to get punters through the door, it is very difficult to avoid the model of the circus or funfair. To ask the question “does that matter” is to highlight the problem.

Art that Never Sleeps etching and aquatint (copper plate) 895 x 590 mm Artist’s Proof. Edition of 8.

This large copper plate is contemporary with Show Girls and again is a visual speculation on the contemporary role of art by showing an imaginary classical sculpture representing “art” atop a building in an imaginary city, modeled on Brisbane.

Cupid Over Queenslander I etching, aquatint and chine collé (shaped plates, upper copper and lower zinc) on rag paper. 630 x 490 mm. Artist’s Proof, one of two proofs, not editioned

Cupid Over Queenslander II etching, aquatint and chine collé (shaped plates) on rag paper. 840 x 490 mm. Artist’s Proof, one of two proofs, not editioned.

Cupids Over Queenslander III etching, aquatint and chine collé (shaped plates) on rag paper. 620 x 490 mm. Artist’s Proof, one of two proofs, not editioned.

Night Cultivation etching and aquatint (copper plate) 590 x 795 mm. 2/6 in this edition.

Exhibition entrance at Hunter College, CUNY, New York.

Copyright © Ross Woodrow --All Rights Reserved