Supplement to the exhibition catalogue

The material here is additional support for the exhibition Etching: Rembrandt’s Legacy at the SACC. A comprehensive catalogue gives an overview of the history of etching from its beginnings in Europe to the 1920s. The focus here is specifically on the seventeenth century, outlining the practices and protocols of the print trade and demonstrating the role of reproductive and independent prints. It will assist in understanding how to read any historical etching and engraving.

The Trade

A short well-illustrated essay on the history of engraving is available on the Met Mus. website and includes this print by Jan Collaert (c.1530–1581) from about 1600. The author says it shows the process of making a copper engraving plate and print, although the variations of the Latin “sculptae” could mean engraving and or etching, especially when combined with “in aes”. Certainly burin engraving is happening on the right table. The plate was generally heated prior to inking so the sturdy metal tray on the centre table most likely contains hot coals but the jug beneath the press and collecting bowl beneath the table could also suggest the process of pouring the acid outlined by Bosse in his seventeen-century etching manual.

During the seventeenth century in Europe printmaking became an enormously important part of the publishing industry with images, mostly engravings, becoming a key element in books, broadsides and maps alongside the well-established reproduction of paintings, drawings and sculpture as individual prints or folios. With diminished Papal control, devotional or religious images faded in importance and with this secularisation of the industry, prints became a powerful medium for knowledge and information dissemination that amplified both their potent political status and economic potential. Prints became big business.

The reproduction of paintings was mostly controlled by publishers who negotiated with artists and engravers or etchers and paid for the copper plates and paper (consequently they often retained ownership of the plates after printing). Unsurprisingly, publishers had significant interest in protecting the copyright of printed images just as the powerful institutions of state, city, monarchy, republic or religious authority demanded some degree of editorial control or oversight not to mention tax benefits. Only a handful of artists of great reputation and resource such as Peter Paul Rubens (1577 - 1640) in Antwerp or Abraham Bloemaert (1566 –1651) in Utrecht could circumvent publishers and employ or negotiate directly with engravers or etchers to produce reproductions of their paintings or drawings. Bloemaert also qualifies to be ranked in the same emerging category of Peintre-graveur [painter/etcher] that was later applied to both Rembrandt working in Amsterdam and Adriaen van Ostade (1610 - 1685) working in Haarlem. Incidentally each of these cities were recognized throughout Europe in the first half of the seventeenth century for the quantity of skilled engravers working there. Amsterdam was also noted for the excellence of its papermaking. Indeed papermills in the Dutch Republic and in Germany had begun to eclipse the once unassailable reputation of Italy for the quality of its paper from mills large and small.

To trade-mark their paper, mills used watermarks, often employing heraldic arms or shields of the region or city where they were located, and much more rarely, royal emblems or crests could be added as a cryptic form of granting privilege to print. In other words the access to that paper gave rights to print. For example the sheets for the set of four prints of the Human Senses by Jochem Bormeester (active 1677-1713) in the SACC show are on hand-laid paper with a watermark of Prince William the V on horseback. A number of Callot’s etchings are on paper watermarked with the initials of Charles IV of Lorraine although those from the Miseries of War series that have watermarks in the SACC exhibition show a modified Fleur-de-lis in a shield, surmounted by crown but lacking any letters underneath. It seems to be a variant of the so-called Strasbourg lily which appears on a number of Rembrandt prints.

Print collectors and curators take a great interest in watermarks since dates and inscribed artists names are difficult to remove, so remain on every restrike or re-print whenever it occurs. However the watermark is often specifically locatable geographically and chronologically. For example the Blazon by Adriaen Collaert (1560-1618) representing the Antwerp Guild of St Luke has clearly engraved in the design the date 1614 but the certainty this is a contemporary printing comes from the fact that the paper has a watermark of a crown surmounting two interlocking C's, dateable to mid-17th century.

To highlight the limits of using watermarks as evidence or endorsement of authenticity or legitimacy for a print it is important to note that the majority of etchings by Rembrandt were not printed on watermarked paper. In fact he pioneered using light strong Asian papers that were rarely watermarked. As demonstrated here most information of value is contained in the inscriptions or so-called address information added to seventeenth-century, and later, prints.

The Life of a Seventeenth-century Print

Protocols and processes were well developed by the mid-century in Europe to facilitate printmaking as a commercial enterprise for artists to make prints as independent works or for folios, illustrations and as reproductions of paintings and sculpture. These can be examined by first taking a single etching designed for a folio, followed by a reproductive engraving and etching both derived from paintings and finally an etching by Rembrandt that bears only thematic relation to his painting/s.

Francis Barlow (1622 – 1704) Cock, Hen and Sparrows 1680 etching, plate c 14 x 18 cm [note a birthdate of “c.1626” is noted in most sources and websites but recently his baptism certificate has been discovered, BM ]

The originating source of most prints in the seventeenth century was an existing painting or preliminary drawing. Natural history related folios often began with descriptive or inventive drawings and as with illustrated books were often issued in stages; six plates being the favored size. Such folios were sometimes sold with two plates printed across a fold to present the folio in a codex format or with single sheets loosely stitched. The SACC exhibition contains several complete examples of large and small prints series that were originally sold in folios; Vernet’s Hours of the Day, Le Brun’s Elements, Lepautre’s Six Grotesque Costume Designs, and Bormeester’s Human Senses, for example. However many of the larger prints were intended to be framed, so are rarely found complete and in good condition. Smaller prints in folios have better hope of survival since in such form they could be safely stored and “perused” as a book. This was the case with the six Various Landscapes etchings by Willem Swidde (1661 - 1697) in the exhibition. They have survived three and a half centuries loosely bound with twine.

Willem Swidde (1661 -1697) Six Various Landscapes etching c 1676 15 × 23.6 cm

The Francis Barlow (1622 - 1704) Cock, Hen and Swallows etching began life in small series that blossomed into a massive compilation of bird and animal prints by Barlow, produced between 1680-94. Presumably after 1695 Barlow largely lost control, but his name is used to sell a folio of seventy prints under the title: “Various Birds and Beasts Drawn from the Life by Francis Barlow” and the Cock Hen and Swallows (now in reverse) becomes the lead plate a subset of the larger series with its title sheet: “Birds and Fowles of Various Species Drawn after the Life in their Natural Attitudes.” As will become evident, the plate is the currency of the folio, so preliminary drawings rarely survive, although fortunately the drawing, in pencil, ink and watercolour, for the etching Cock, Hen and Swallows dated 1680 has survived and is now in the Tate Gallery in London. As is always the case when a drawing is copied directly onto the copper plate, the resulting print is a reverse of the drawing. A British Museum biography of Barlow acknowledges that, although he was principally a painter, he was also “one of the finest English etchers of the century, as can be seen in his plates for Benlowe's 'Theophila' and his greatest achievement the 1666 edition of Aesop.” However he often employed leading engraver/etchers of the day to etch his plates such as this example etched by Francis Place. Engravers started signing plates with their initials or marks from the 1450s. The text beneath the image on this plate gives the key facts of its making using the abbreviations and phrases that began to emerge in the lower margins of prints around 1500. Latin was favoured, although other languages and conventions in this so-called print address system, for authorship and publishing privileges can be confusing. Rembrandt only briefly used any of the established editioning and publishing abbreviations developed by the beginning of the seventeenth century and simply added initials or signature directly on, or in the field of, the plate. In at least two cases (one, Three Oriental Figures, is in the SACC exhibition) he failed to make the necessary reversal of his signature on the plate or to burnish and correct it before printing. This Barlow print follows the common convention of listing the creator, maker and publisher. The Latin abbreviations are explained below.

Fra. Barlow delin. Francis Barlow [delineator or deliniator] “has drawn” this.

Fra. Place fecit. Francis Place [fecit aqua forti,] “etched in acid” {note “fecit” can often simply mean “has made” but for an engraving the term will usually be “incise”, “inc”, “schul.” or the confusing “schulp.”} When an extensive caption text is added a specialist in engraving reversed letters would be employed and acknowledged with ( écrit “has engraved the letters”)

P.Tempest Excut'd'. Pierce Tempest [excut., excutit, exk., from the Latin verb ‘excudere’] “has published”

A most comprehensive listing of abbreviations can be downloaded in PDF from Ad Stijnman

An etched or engraved copper plate could easily generate an edition of several hundred prints before any worn lines needed refreshing with an engraving burin. After many editions the plate could be carefully re-etched with addition of a new ground and judicious application of acid, however this practice really only became a viable option in the late eighteenth century when rollers could be used to apply the ground. Into the nineteenth-century techniques of stereotyping a plate or by the end of that century, facing old plates with steel, made for eternal plate life. However, protecting the ability of the plate to create large editions was not the issue in the seventeenth century, as the example of Barlow’s etching shows. The problem was having command of copyright particularly across borders. The original drawing that generated this print loses its prime value when an edition is printed since each print can act as a new source to generate another plate and another pirate edition, as has happened here, along with a “legitimate” new edition for another publisher in another country or jurisdiction.

The following images reproduce the preliminary drawing and etching by Barlow from 1680 (the etching is a mirror reversal of the drawing). Following this is a reprinting of the plate, published in London in the 1690s, now in the British Museum. Next is a copy of the image now in the Tate Gallery, published in London as a new plate with some additions; and finally, another copy from the original Barlow print now in the Rijksmuseum and printed from yet another new plate that does acknowledge Barlow as the original source (F.B.).

The addition of the new bracketed inscription “Sold by Iohn King at the Globe in the Poultry' and King's number 28.” makes it clear that this is a reissue of the plate and leaves all other acknowledgements in place, although the folio number has been removed from the top right with a new one at the bottom. John King was a large publisher who had purchased this and many other seventeenth-century plates from artists and engravers and passed the collected plates and business on to his son. However the copy of the print in the Tate which only acknowledges Barlow as the originating artist is clearly a new plate which has significant additional tonal work added (note the different sky) with most of this added as engraving, it seems, rather than etching. In addition, it is a reverse of the original plate which is the common outcome when a new plate is made from a print as source. The same reversal applies to the version of the image in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. However this copy of the original image does acknowledge the original artist F. B. along with the new artist J. Gole exc; This is the Dutch artist Jacob Gole (1660-1737) who published and engraved the work; also noting his copyright privileges in Holland with cum privileg. ord. Holland. &. “with privilege for the Dutch Republic”

The description of this print in both the British Museum and the Rijksmuseum catalogues refer to the swallows as chickens. This is an inexcusable lack of observation considering the folio this print belongs to includes several prints with chickens and indeed finches or swallows along with doves - in one case all of these in the same print by Barlow and Place as above. Such a description also misses the subject of this depiction; namely, the usual farmer’s drama at poultry feeding time when wild birds would quickly learn the time of the ritual and swoop in, the rooster’s posturing is aimed at the inevitable, invincible intruders. (This also serves as a reminder of the dangers of reading the Latin text and not the print image)

The Reproductive Print

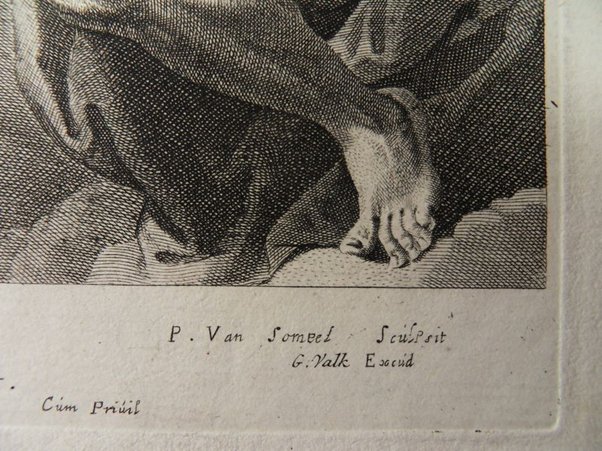

The most demanding and lucrative work for engravers and etchers was commissioned or sponsored reproduction of paintings by celebrity painters such as Peter Paul Rubens (1577 - 1640). The first of the Ruben’s examples here is an engraving by Pieter Van Sompel (c. 1600–c. 1650) and the second is an etching by Pieter Soutman (ca. 1580–1657). In fact, Pieter Soutman was closely involved in the publication of both prints and most probably also involved in the painting of the originating paintings. Soutman collaborated with Rubens in the period when both these paintings were made, Pieter Van Somel had been Soutman’s pupil in Haarlem, and the first printing of the engraving of Ixion Deceived by Juno had Soutman listed as publisher (and probably drawer), suggesting he delivered a drawing after the painting back to Van Somel in Haalem to complete the job of engraving the print around 1620. The Louvre catalogue [which has a clear description of the characters in this Ixion Juno saga] suggests that Rubens corrected the drawing after completion. At least, when the drawing was acquired by the Rijksmuseum in 1999, that was the received wisdom, however a visit to the Rijksmuseum entry on the drawing currently reveals that Van Somel not Soutman is now given authorship. Ixion Deceived by Zeus and Hera, Pieter Claesz. Soutman (rejected attribution), Pieter van Sompel (attributed to), c. 1615. The justification for this reattribution notes: “over a fairly hesitant sketch in black chalk and grey wash, a much more skillful draughtsman – probably Rubens himself – introduced all manner of additions and corrections.” The drawing actually looks more like a preliminary drawing for the painting (although it does have transfer marks on the outlines) but the idea that this level of skill was beyond Soutman is unstainable as an argument looking at any of his work from that period. The drawing is reproduced below. By the end of Ruben’s life in 1640 when the large etching was made, Soutman was back working in his home city of Haarlem and although he acknowledges Ruben’s authority over the image, P.P.Rubens Pinxit, he makes his primary role emphatically clear, claiming invention, drawing, publishing and copyright for the work; P.Soutman Inuenit Effigiauit et Excud. Cum Privi. This may well have been justified considering his prodigious skills across mediums but the cramped positioning of the last inscription after the confusing Latin verse suggests it was added after initial layout and may well have been prompted by news of Rubens’ demise. This assumes, as would be logically expected, since he is added as publisher in both cases, that Soutman owned both plates. Some time after Soutman’s death the engraved plate of Ixion Deceived by Juno passed into the hands of the publisher Gerard Valck (1651/52–1726) in Amsterdam since the impression shown in the SACC exhibition has a watermark indicating it is from about 1680 and Soutman’s name has been removed, with Valck recorded as the publisher.

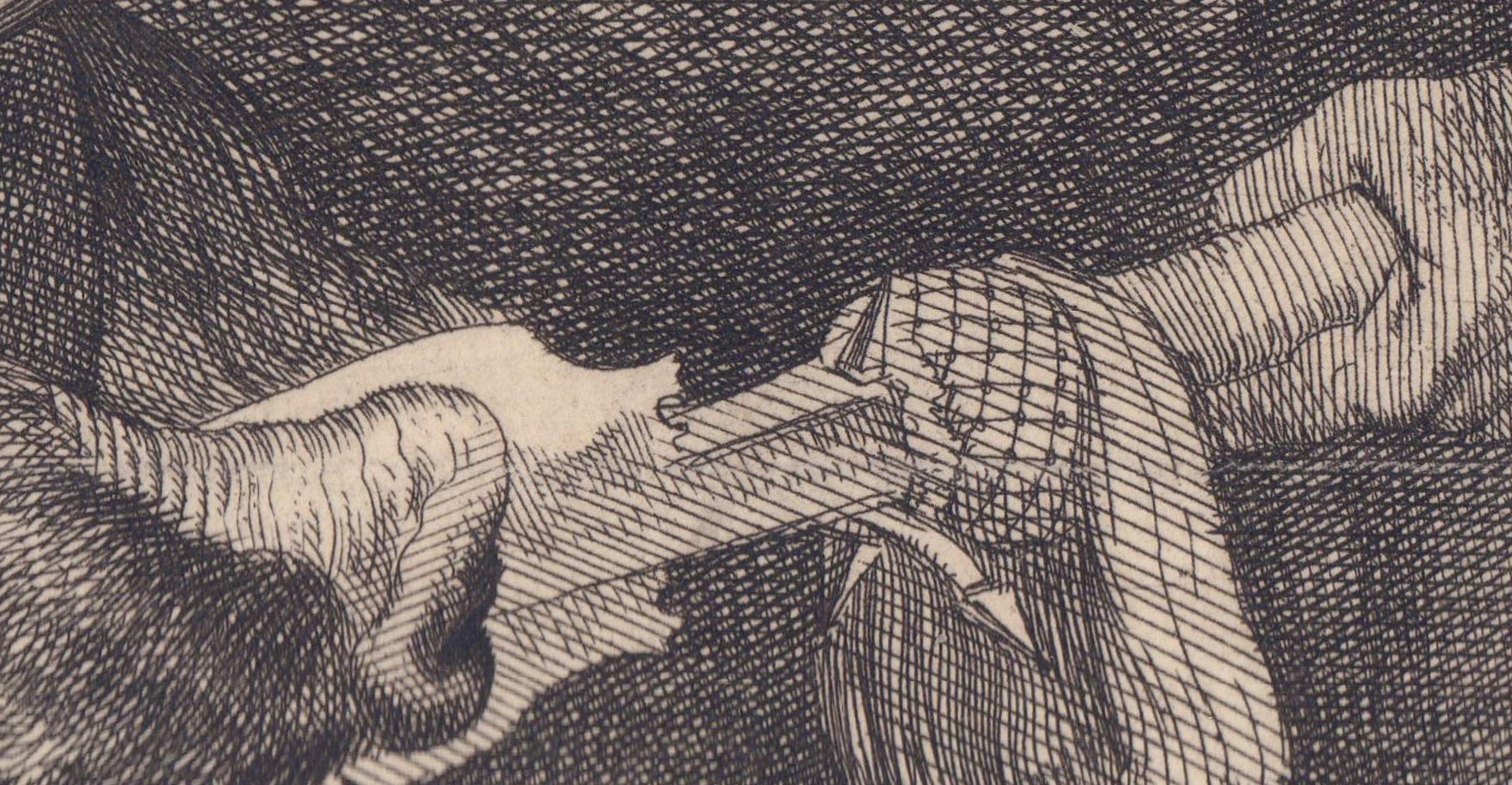

Distinguishing between an engraving and etching can be be difficult sometimes without a magnifying lens or loupe which generally makes obvious the sharp clean edge of an engraved line as opposed to the softer-edged trough bitten with acid. Detecting the nature of the etched or incised lines with the naked eye, is especially difficult for seventeenth and eighteenth-century prints since many etchings were finished off with an engraving burin. Some details from the above engraving and etching will act as a general guide. The top three are from the engraving where the linear hatching and cross-hatching are almost always characterised by a much more formal, regular, often geometric, patterning which is rarely the case with an etching as shown below. In other words the white patterns of squares or lozenges are regularly distributed. This is because an engraver controls the direction of each line as it is cut into the copper and with a mass of parallel lines the previous line acts as a guide for the next and so on. In the next century engraving machines would facilitate the engraving of parallel lines removing much of the tedium for backgrounds. Few etchers could precisely control the depth or thickness of a line drawn into a dark ground and moreover the ground may, and often does, fall back across the drawn line to thwart the acid reaching the copper. This leaves minute or obvious gaps in the lines, something that doesn’t happen when an engraver is watching the burin plough up the sliver of copper for every line. Of course etchers often touch up the lines after the etch when this happens but many can be missed as with the examples just in front of the snout of the pig in the detail below. The odd strip of blurring below the hand on the right of the etching detail is a sort of static that only occurs when the acid leaks under lines placed too close together or where the ground has become loose or lost, creating what is called foul biting. This does not happen with engraving. However in the contest for free-flowing line, drawing a burin across a plate is no match for drawing with a fine needle in a soft or hard ground. This freedom is evident in the lines at the top of the spear shaft where the velocity of the drawing is obvious and the row of squiggled circles is a quick few minutes work, but a bridge too far for an engraver with a burin in hand, at least to create this spontaneity of line. However as slow as the process was, engravers had the huge advantage of working in real time and could see immediately the result of a stipple texture or the degree of definition needed for a contour line. Etchers obviously had less immediate control over tonal textures and densities (at least before the development of aquatint) and this is why many engravings have much clearer definition of individual elements or motifs in the print. Deep, dark tones using techniques of mezzotint only came into effective use towards the end of Rembrandt’s career as an etcher and his experiments with Sulphur tint created tone of very limited density.

The biggest problem for reproductive engravers and etchers were interpreting in grey-scale tone the overlapping objects and surfaces represented in the painting where contiguous colours of close to the same value were used to define contour as, for example, a light blue meeting a grey or flesh-colour. High value intense red, for example, in the veil the winged Iris throws over the embracing couple would pose special problems since it is also in a dark shadow area of the painting. The right hand detail below shows how skillfully Van Somel has overcome the issue of interpretation of colour to a tonal and linear environment and used the optical logic of counter change and the illusion of simultaneous contrast to define the back contour of the real Juno.

The Independent Print

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) The Baptism of the Eunuch 1641 etching with touches of drypoint, plate 18.2 x 21 cm

Rembrandt’s etching of the Baptism of the Eunuch is typical of most of his prints with simply a signature added in the plate although in this case, less typically, a date is included. The date, 1641, is long after his first painting on the theme in Leiden around 1626. That painting generated two prints, an etching and engraving. This was during the period in the early 1630s when he collaborated with Leiden based etcher Jan van Vliet (c.1600/1610-1668?) They published prints together and with the Amsterdam based dealers Hendrik Uylenburgh and Claes Jansz Visscher.

The biblical story of the baptism of the eunuch is from Acts 8:26-39. While walking along the road from Jerusalem to Gaza, St. Philip is divinely compelled to accompany the passing entourage of the Treasurer of Ethiopia, a eunuch serving under Candace, Queen of Ethiopia. Philip joins them and preaches to the official and his servants, and when they come to a small body of water the eunuch asks Philip to baptize him.

The inscription below Jan van Vliet’s 1631 etching: “RH v.Rijn inv. JG.v. vliet fec. 1631" confirms the primary status of this image as no doubt a reverse mirror record of Rembrandt’s painting. At almost 50 x 60 cm it is also a very large plate. (The British Museum holds three copies of this etching).

Copies or workshop versions of the lost painting exist such as the one shown below. The Kremer Collection has recently claimed their copy is an authentic Rembrandt and workshop painting from 1626. An entirely different if somewhat unconvincing signed and dated version of a The Baptism of the Eunuch, 1626, is held in the Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht. However, in 2020 another version by Rembrandt has been discovered that resembles the later Vliet engraving. The Rembrandt authority, Gary Schwartz, has published a small book A Rembrandt Invention: A New Baptism of the Eunuch, 2020 and makes the point elaborated on his Webportal that none of Rembrandt’s depictions of the theme follow the Bible description where the two protagonists stand in the water (not such a major revelation, that Rembrandt didn’t read his Bible and instead looked at other painters). For discussion see the Gary Schwartz website.

However a most important point to make is that Rembrandt’s 1641 etching bears only passing resemblance to the two earlier paintings and prints, leaving behind the pyramidal and formal staged compositions for a much more naturalistic suggestion of depth, gesture and movement. Rembrandt’s investment in the qualities of etched lines is evident, reflecting his liberation in making an independent print, different in every way to the reproductive etching and engraving of his earlier investigation of the theme.

Copyright © Ross Woodrow --All Rights Reserved 2023 -24